Well, after a long hiatus of over a year, I've decided to put up another post here in my collection of anecdotal tales of Toronto's history. The patriotic inspiration for this was the fact that another Canada Day is upon us. I'm only one year overdue for posting in time for Canada's 150th, which took place last year, but hopefully any reader will find this almost as informative and entertaining for Canada's 151st.

The title of this post, referencing "Canada Day" is of course misleading. Traditionally, July 1st had most commonly been known as "Dominion Day". This alluded to the British North America Act, which made reference to the country as a Dominion. There were suggestions to change the name of the holiday to "Canada Day" as early as the 1940s, but it wasn't officially changed until 1982. Although some traditionalist Tories and historical diehards may still refer to the day as Dominion Day, most people these days of course refer to July 1st as Canada Day.

____________________

____________________

So, to begin, back in 1861, a few years before Confederation, Toronto had a population of 65,000. We were the most inhabited city in the Province. Only Montreal, with its population of 90,000 people, was bigger. And with Canadian Confederation, we were set to become the capital of the brand-new Province of Ontario. An article in the Globe newspaper, operated by George Brown, one of the Fathers of Confederation, laid out the festivities held in Toronto to celebrate the creation of Canada, on Monday, July 1st, 1867.

The article reported how bells were rung at St. James Cathedral at midnight, as June 30th became July 1st, to “convey the joyful news to the city that the important era had arrived”, as the newspaper put it. The article went on, “Toronto has bestirred herself to make the holiday befitting the occasion … sufficient is announced to secure that the day shall be remembered among us as an eventful one in our history.”

The old Cathedral Church of St. James had been destroyed by fire in 1849, and the main body of the church was re-opened to the public in 1853. As the photograph of the cathedral in 1867 shows, the spire was not yet complete, and wouldn’t be completely finished until 1874. But enough of the spire had gone up to house the bells, which had arrived in Toronto in 1865, two years before Confederation.

|

| The Cathedral Church of St. James, at the northeast corner of King and Church streets, in 1867. |

The first set of bells for the Cathedral were lost in a shipwreck off Rimouski, Quebec. A new set of nine bells were imported from the United States, and made the final leg of their journey along King Street by horse-drawn carriage in 1865. When they were first rung at Christmas that year, an article in the Globe newspaper wrote how “the heart of many an old countryman was warmed again by those old familiar sounds which delighted him in years gone by in his native land.” These same bells are still used 153 years later, in 2018.

|

| Transporting the new bells for the Cathedral Church of St. James along King Street, Toronto, 1865. |

A professional bell ringer, one Mr. Rawlinson by name, was on duty at the Cathedral on July 1, 1867. The Daily Leader newspaper had a little bit more to say about the historic ringing of the bells on that day. “The new Dominion was hailed last night as the clock struck twelve by Mr. Rawlinson ringing a merry peal on the bells of St. James’ Cathedral, the effect of which was very fine, in the otherwise solemn stillness of the night. Even at that late hour large numbers of persons were brought into the streets by the chiming of the bells and thousands there remained at their open windows to enjoy the pleasures of listening to the first musical performance of the Province of Ontario. The bells had scarcely commenced chiming when the firing of small arms was heard in every direction.”

The small arms fire was thanks to a detachment of the 10th Battalion, Royal Regiment of Toronto Volunteers. They assembled outside their drill shed and hoisted the Royal Union Flag, as well as their own Regimental Colours. The Royal Union was given a 21-gun salute at about 4 o’clock in the morning, no doubt to the great delight of the neighbours. The Royal Regiment of Toronto would eventually become the Royal Regiment of Canada.

At six o’clock in the morning, a large ox was put on a spit at the foot of Church Street. One Captain Woodhouse, who commanded a ship called Lord Nelson, was in charge of the patriotic barbecue. The animal had been purchased from a butcher named Joseph Lennox, up in Yorkville. The Globe noted that the ox would take most of the day to roast, and leftovers would be distributed amongst the city’s poor.

The Daily Telegraph newspaper also noted that parts of the ox were given to two different charities for children. The Protestant Orphan’s Home had opened in 1854, on Sullivan Street, between Queen and Dundas streets. It struggled to accommodate the flood of immigrant children to Toronto, or those who had lost their parents to cholera and the other lethal diseases that swept through Toronto at the time.

|

| Protestant Orphans Home, Sullivan Street, Toronto |

The House of Providence stood on Power Street, south of Queen Street. Opened in 1857, it was operated by the Sisters of St. Joseph and the Roman Catholic Church. Nearly always full, the institution would eventually quadruple in size to provide for about 700 residents, including the unemployed, orphans, the elderly, immigrants and widows. Some stayed for a few days, while others were there for years. The House of Providence lasted for over a century before it was demolished in 1962 to make way for the Richmond Street exit from the Don Valley Expressway.

|

| House of Providence, Power Street |

Toronto’s church-going faithful also sought out their own edification when Canada became a country on July 1st, 1867. Some assembled at 9:30 in the morning, in the lecture room of the Mechanics Institute at Church and Adelaide streets. They were there for a meeting of the Toronto Branch of the Evangelical Alliance, and “Christian persons of all denominations” were “invited to attend at that hour to invoke the divine blessing of the new Dominion”.

The Toronto Mechanics’ Institute had been built in 1853. Paying members could attend lectures and courses and use the library. In 1883, the institute was given financial support by city council, at a time when no other city in Canada had a completely free public library. So, the Mechanics’ Institute became the nucleus of the first public library system in the country. The building was demolished in 1949.

|

| The Toronto Mechanic's Institute, at the northeast corner of King and Adelaide streets |

Oliver Mowat was the most notable speaker at the religious rally held at the Mechanics’ Institute on July 1st, 1867. He was vice-chancellor of Evangelical Alliance, a Father of Confederation, and a rival of Sir John A. Macdonald. Mowat wanted strong provincial autonomy, where Macdonald envisioned a very centralized federal government for the country. Mowat served as Ontario’s third premier for 24 years, from 1872 until 1896. He then served as Ontario’s eight lieutenant-governor, from 1897 until 1903.

Mowat was Ontario’s first great leader, and made the province the richest in Canada. It was under Mowat’s leadership that Ontario’s agriculture was modernized, industry was expanded, areas like education and science were cultivated, urban social problems were addressed, and electoral reforms like voting by secret ballot were introduced. If Macdonald was the “Father of Canada”, then Mowat was the “Father of Ontario”.

|

| Sir Oliver Mowat (born July 22nd, 1820, died April 19, 1903) |

But, back to Toronto during the celebrations of Canadian Confederation. They continued all day long. A military review and parade was held on public commons along Spadina Avenue, south of College Street. The afternoon saw a picnic and festival in aid of the new St. Patrick’s School House, and a church on Dummer Street. The Horticultural Society put on an evening concert and dance, with music supplied by two military bands.

|

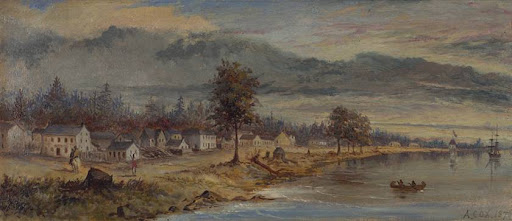

| The Public Commons, Spadina Avenue, south of College Street, hosted a military review and parade on July 1st, 1867. |

Fireworks were set off at Queen’s Park at about 9 o’clock that night, and the park itself was illuminated by lantern light. The area was still mostly a public park at this point, with the parliament buildings still down at Front Street. Today’s legislative assembly wasn’t built on this spot until 1893, and the only building in the park was King’s College, which had been abandoned in 1859 in favour of University College.

The Daily Telegraph newspaper wrote up a good review of Toronto’s first ever July 1st fireworks display, which were set to the tunes offered by two military bands. The paper said, “The great event of the day … was the display of fireworks in the Queen’s Park during the evening. It drew together an immense crowd. The display was the finest of the kind ever witnessed in Toronto and gave universal satisfaction. Several of the pieces were very beautiful and appropriate.”

Monday, July 1st, 1867 was a public holiday across the new Dominion. Businesses were closed, and Toronto celebrated with public musical recitals, choirs, military parades, pageants and picnics, and topped it all of with night time fireworks. At the heart of it all, it doesn’t really sound too different from how we celebrate July 1st these days.

Sure, those partygoers from 151 years ago wouldn’t recognize the Maple Leaf Flag, and they’d probably be more than a bit startled with what we can do with modern day fireworks. They’d have no idea what a “Canada Day” actually was. But I found it curious that, in spirit, anyway, a lot of our public observances are the same as they were 151 years ago now.

____________________

____________________

However you are commemorating Canada Day this year, I hope it's a fun and relaxing one. A simple internet search will reveal a number of "Top Ten" lists of special concerts, fireworks displays, markets, food festivals and activities that are available over this long weekend. As usual, my choice is mostly for the historical, and three of the City of Toronto's historic sites are putting on special events. These are Fort York National Historic Site, Mackenzie House Museum and the Scarborough Museum.

Canada Day at Fort York National Historic Site

"In addition to flag raising and flag lowering ceremonies, the Fort York Summer Guard, dressed as members of the Canadian Regiment of Fencible Infantry (circa 1815) will perform demonstrations of musketry, artillery and fife and drum music. Children can enjoy a drill activity, music classes, and a scavenger hunt. The Fort's volunteer historic cooks will demonstrate period-specific cooking methods and recipes in the historic kitchen."

|

| Celebrate Canada Day at Fort York National Historic Site |

Canada Day at Scarborough Museum

"Looking for a unique and memorable Canada Day? Scarborough Museum hosts their annual celebration in Thomson Memorial Park. Demonstrations include historic blacksmithing, spinning, weaving and leather working. Don't forget to check out the Scarborough Historical Archives tent and browse through archival aerial photographs, maps, and lots of information not he history of Scarborough. The museum's annual pie eating contest is also back by popular demand. Finally, enjoy celebratory Canada Day historic treats and stroll through the vendor markets."

|

| Celebrate Canada Day at the Scarborough Museum |

Canada Day at Mackenzie House Museum

Celebrate Canada's birthday with a visit to Mackenzie House, the home of Toronto's first mayor! Visitors can use the 1845 press to print their own Maple Leaf postcard.

|

| Celebrate Canada Day at Mackenzie House Museum |

____________________

For frequently updated historical photographs of Toronto, follow me on Instagram!

My Instagram ID is "fiennesclinton"